Cartographers of Power

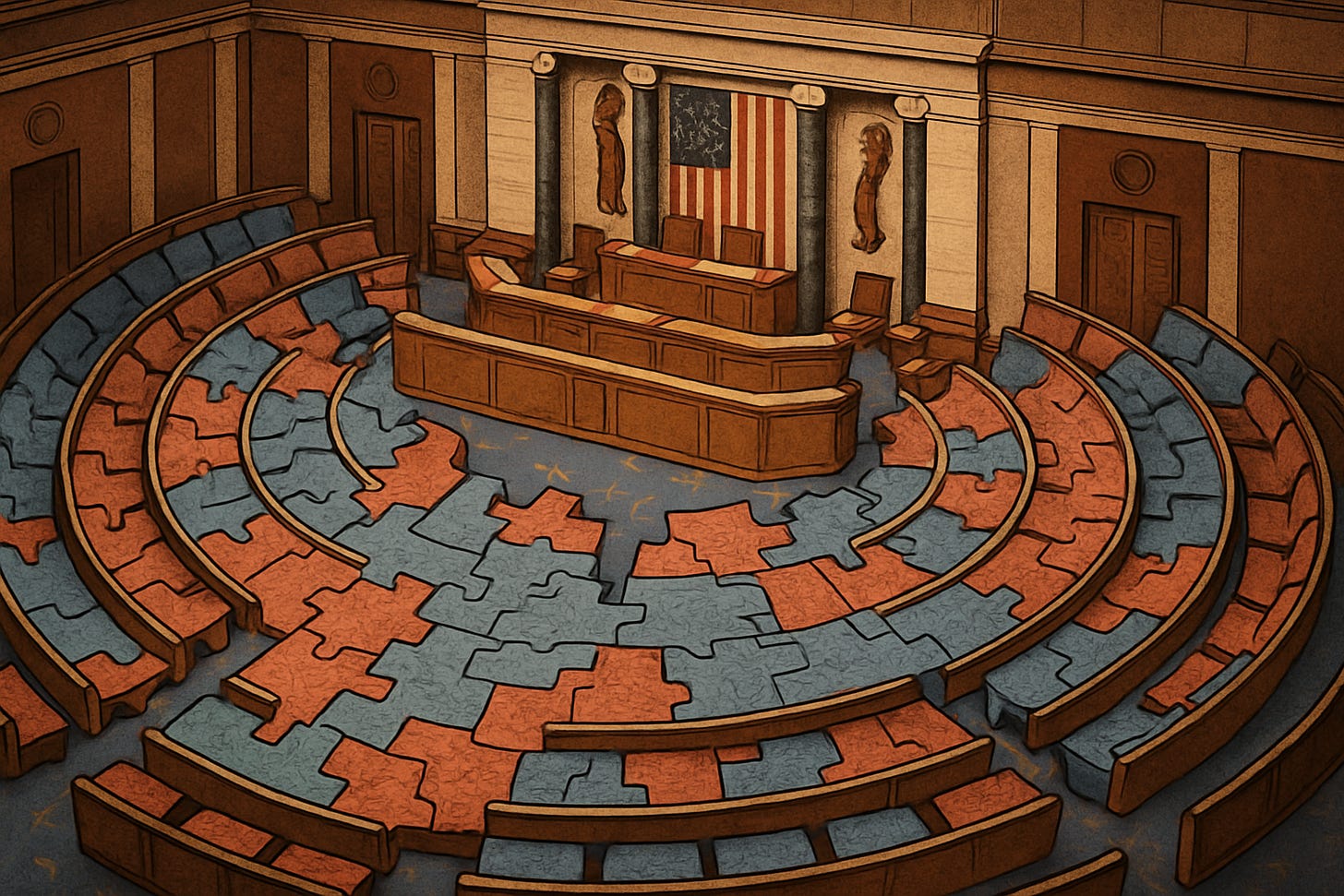

States Rewrite the House Map

The next House of Representatives will look very different from the current should off-cycle gerrymandering efforts come to fruition. The redrawing of congressional districts in Texas could flip five seats from Republican to Democratic – that legislation is expected to be shortly signed into law. In response, California is looking to redraw its congressional districts, potentially moving five Republican seats into the Democratic column. Other states may be getting into the fray, many pushed by Pres. Trump.

It is difficult to assess whether there will be a net change in the number of Democrats and Republicans elected to Congress. One outcome is states will have more politically homogeneous representation in Congress. The gap between party affiliation of elected officials and that of voters will grow. Many incumbents will lose their seats. State caucuses will be less able to advocate for their state's interests when the party controlling the national government is different from the party that dominates the state. We may also see changes in the number of minority representatives in Congress. All of these consequences are prompting academics and some politicians to dust off pet proposals to address gerrymandering.

One proposal receiving renewed attention is expanding the size of the House of Representatives with the stated purpose making weirdly-shaped partisan majority districts harder to draw. Proponents argue that doing so would make more congressional elections more competitive, work around gerrymandering’s historical permanence, or return the House to its community-oriented representational roots.

This last point echoes the arguments of academics over recent years that smaller districts would improve the quality of representation for constituents as members regained the ability to have granular knowledge of their districts. It’s also a reform Congress can implement through legislation. In fact, Reps. Sean Casten and Earl Blumenaeur both introduced bills to replace the 1929 Permanent Apportionment Act, which permanently capped the House of Representatives at the same number of voting members it has had since 1910, with new apportionment systems that enlarge the chamber and steadily increase its number of seats as the U.S. population grows. We have grave concerns about the merits of that proposal, but will leave a discussion about the institutional impact of expanding the House for another day.

Gerrymandering proposals are useful reminders that Congress has the final say in how it apportions seats in the lower chamber. Like partisans in state legislatures trying to maximize their party’s advantage, members of Congress are self-interested actors in using this privilege. In fact, the Permanent Reapportionment Act and the 1842 Apportionment Act of 1842, which mandated single-member districts, were designed to lock in specific incumbency advantages. Today’s gerrymandering wars, driven by hyper-nationalized partisan election cycles, create a different type of risk even for members in seats that will remain safe. Their act of self-preservation wouldn’t be House expansion, but by eliminating single-member districts.

As they designed the Legislative branch, the framers had few examples to draw upon as models for how to select representatives. Delegations held one collective vote per colony in the Continental Congress and per state under the Articles of Confederation. Colonial legislatures typically drew representatives from towns or counties. Other national representative bodies of the type they were creating didn’t yet exist. The framers simply left it to the states to determine how to fill the seats the Constitution apportioned to them, reserving congressional power to intervene as a backstop.

Some states decided to stick with a geographic-based system and immediately used the power vested in holding the districting quill. Debate about the Constitution had created new political factions. Faction leaders recognized that drawing lines through municipal boundaries could create advantages for their candidates. It was not something the Constitution’s authors anticipated: the Virginia General Assembly tried (unsuccessfully) to draw James Madison himself out of the first Congress by making his district more strongly Anti-Federalist. It was, however, something that they as politicians quickly embraced. Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry, whose 1812 map is the inspiration for the gerrymandering moniker, attended the Constitutional Convention.

But as Lee Drutman notes, not every state chose this path. Six of the original 13 states implemented multimember or mixed district/at-large systems for their congressional seats. Because these systems also awarded seats to the candidates receiving the most votes, they often delivered even more drastically unrepresentative results than even gerrymanders. In the 1820s and 30s, the Democratic Party could win two-thirds of House seats with just over half the popular vote through multimember districts.

As partisan competition intensified, states often whipsawed between single-member and multimember districts depending on how which system benefitted the party in power. But voter engagement in the antebellum period, driven by the vital importance of party patronage systems, meant that neither system created true safety for incumbents. Either one could allow electoral tsunamis for the opposition. Congressional majorities started to swing wildly in the 1830s and 40s. The Whig Party tried to stabilize its place in the electoral system through congressional action. Its 1842 Apportionment Act mandated single-member districts, which offered some safety for some of its urban strongholds from Democratic waves. It wasn’t enough, however, to save the Whig Party from irrelevance and ultimate extinction in the explosion of political activity around slavery.

Our current computer-driven system of gerrymandering has eliminated anything resembling antebellum electoral noise, winnowing down the number of competitive districts to the bare minimum. Most of the real competition takes place during party primaries. The impact of that shift has been stark: since the turn of the 21st century, intraparty competition has made the Republican Party increasingly conservative while the Democratic Party has remained relatively unchanged ideologically.

More moderate GOP members are being squeezed out of Congress as a result. Since Donald Trump’s first election, 10 Republican members have lost primaries and 68% of ideological moderates overall have left office. Those elected since 2017 are significantly more conservative than the members they replaced. With Trump as the focal point of the congressional agenda, the 2026 midterms are likely to continue to winnow non- hardcore MAGA candidates.

For incumbent Republican members reluctant to ride the MAGA train (and what centrist Democrats have survived redistricting), the current electoral system of contested primaries in safe districts provides limited cover.

Given the intensifying concentration of Democratic voters in cities and Republican voters in rural areas, there’s little to suggest that adding congressional seats will reduce partisan stacking. Institution-minded incumbent Republicans will continue to battle in first-past-the-post, low-turnout elections through a media environment strongly favoring their conservative opponents.

One way for them to survive is to change to a proportional representational, multimember district system. This offers moderates – or any minority faction within a party – a pathway to office without having to win every election outright. This is an approach that a number of countries descended from the British parliamentary system have adopted.

Modern proposals in the U.S., like the one advanced in the Fair Representation Act, H.R. 4632, address the inequities of single-member districts and the 19th century multi-member gerrymandering abuses by crafting congressional districts with 3-5 members and using ranked choice voting for their selection. It is possible for Congress to establish a fairer, more representative system that makes it harder for majorities to rig the results to favor their faction/party.

The Whigs didn’t have this option as it was being developed around the time they were making their last-ditch effort in Congress. If history is a guide, major structural reform to congressional elections is most likely to come from political elites looking to live to fight another day. It would arise from the incentives of the members in the House of Representatives to preserve their existence and power. A switch in systems to PR would also be generally beneficial to the institution.

It does not look like it is in the cards any time soon unless there is some innovation that takes place in how the House chamber operates. Until then, sadly, we can expect to see inequity in representation increase in the lower chamber as state legislatures solidify political control in a single party.

APPORTIONMENT

We are now in range of pocket recissions if the Administration attempts the unlawful maneuver. Time likely has run out for advocates seeking to force the White House to disburse billions of dollars in withheld foreign aid by the end of the fiscal year. A federal Appeals Court ruled that only the Government Accountability Office has standing to sue under the Impoundment Control Act. GAO had decided to wait for the results of advocacy groups’ lawsuits before filing its own.

A court order in a different lawsuit, meanwhile, has revealed the scope to which the Office of Management and Budget is trying to impose political control on disbursements of federal funds. Under the order, OMB released apportionment records with footnotes explaining permissions required to federal agencies from OMB to authorize federal spending, including compliance with anti-DEI executive orders. The last time we checked, federal law is paramount over EOs.

OMB also finally complied with another court order to restore data on its apportionment website, which it had previously taken down in defiance of a 2022 law. CREW and Protect Democracy had sued OMB to restore the public-facing website. Protect Democracy also has developed its own, more user-friendly version of the website at OpenOMB.org.

The Supreme Court Thursday allowed $783 million in grant cancellations at the National Institutes of Health to stand as five justices found plaintiffs should have filed in federal claims court instead. The 5-4 decision overturned district and appellate decisions that had put the NIH's "not reasonable and not reasonably explained" hold on hold.

Senate appropriators, meanwhile, have added report language to the text of bills moved by the committee to include more specific directives to OMB on spending by several agencies to avoid repeating apportionment conflicts in FY 2026. Agencies generally defer to report language adopted by appropriators, but instructions issued by OMB and actions by the administration to ignore that language means legislators seek to write it into law. Ignoring enacted law would create additional risks for administration officials.

SECURITY DEMANDS

Taxpayers are providing millions of dollars to provide security to Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s ex-wives’ houses. His requests for personal protection from the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division, meanwhile, has been so large the agency has pulled officers off criminal investigations. Historically 150 of the agency's 1,500 serve on VIP detail; now there are more than 400.

Coordinating with the new federal crime task force in DC is one part of the job that the new U.S. Capitol Police Chief Michael Sullivan didn’t anticipate. He told Roll Call that he’d be open to looking at publicly releasing the number of credible threats the department receives, which his predecessor, J. Thomas Manger put in the hundreds. Drilling down into such data would be very helpful in contextualizing the threat data that the department currently releases, which counts 9,474 threatening or concerning statements directed at staff, members, and their families in 2024.

ODDS AND ENDS

The Library of Congress will hold its annual Congress.gov Public Forum on September 30th, 2025, from 1-3:30 PM ET. The hybrid forum will allow people to attend in person at the Library of Congress’s Jefferson building or online. Here is how to RSVP.

These annual forums are required by congressional appropriators and provide the public an opportunity to hear updates to Congress.gov over the previous year and also allow the public to provide “feedback about how we can better service your legislative information needs.” This can include suggestions for new information published on Congress.gov, improvements for current features, and changes in the way information is made available to the public.

True blue Senators are ignoring President Trump’s demand that they eliminate “blue slips,” which minority members can use effectively to veto nominees for district court judge and U.S. Attorney in their state. Even weak forms of patronage are sticky.

My project, your pork. Several different factions within the House majority, including the Main Street Caucus and House Freedom Caucus, are pushing leadership to allow community project funding (i.e., earmarks) in any continuing resolution passed before the October 1 federal funding deadline. HFC’s Andy Harris, however, wants a flat-funded CR along with the earmarks and additional recissions. It's tough to figure out how that computes.

Modernization update. The text for a Committee on House Administration Modernization and Innovation Subcommittee roundtable discussion in March is now available on Congress.gov. The closed-door roundtable explored new ideas for innovative projects in CAO, the House Clerk’s Office, GPO, and OLC.

GPO profiles. GPO offered the perspectives of one of its newest hires, a recent graduate program recruit of the Library Services and Content Management team, and the 35-year vet running its Congressional Record Index Office.

Hardcovers. Back in the 80’s earning hefty book royalties from bulk sales to politicos was the kind of thing that got a Speaker of the House a target on his back and the boot from his office. Now, dozens of members utilize the book writing loophole to augment their congressional salaries. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene earned slightly more than her day job pays through her book, which was published by a company co-founded by Donald Trump Jr.

CMF awards. The Congressional Management Foundation announced the winners of its Democracy Awards, given in seven categories to members and staff from both parties. CMF will host an awards breakfast on September 18 in the Cannon Caucus Room.

Hispanic history event. The United States Capitol Historical Society and the Latino Coalition will host a day-long symposium “Commemorating Hispanic History in Congress” on October 7 from 9AM to 4PM in the Cannon Caucus Room. Register for the event at this link.

Increasing the number of seats in the House would not decrease gerrymandering. Instead, it would provide more opportunities.

To prove the point: every state has more legislative seats than Congressional seats. Yet states are perfectly capable of drawing extreme legislative gerrymanders. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project's grading system awards plenty of D/F grades to legislative plans. See gerrymander.princeton.edu and https://djclpp.law.duke.edu/article/the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly-wang-vol20-iss1/