Insider threat

It’s pretty much over for the Legislative branch with the Senate’s 53-47 confirmation of Russell Vought as OMB director. I say this not just because Vought’s unconstitutional views of impoundment will destroy Congress’s most important authority, the power of the purse.

I say it because Senate appropriators, the people who are the most threatened, the most institutionalist, and the most “bipartisan” members of Congress, failed to block his nomination or do much more than express “concern" over impoundment.

They don’t need to worry about frequent elections, they have decades (centuries?) of combined experience, and know how to defend their prerogatives. These are the boldface names. To give you a taste, in order of seniority, they include Sens. Susan Collins, Mitch McConnell, Lisa Murkowski, and Lindsey Graham.

If Senate Republican appropriators don’t stand up against impoundment, what hope do we have for other senators to do so on this or any other issue?

Here’s what Patty Murray, the ranking member of the Appropriations committee, had to say on the consequences of the White House moving forward with impoundment:

Democrats are, as always, committed to responsibly funding the government, but it is extremely difficult to reach an agreement on toplines — much less full-year spending bills — when the president is illegally blocking vast chunks of approved funding, when he is trying to unilaterally shutter critical agencies, and when an unelected billionaire is empowered to force his way into our government’s central, highly-sensitive payments system [at the Treasury Department]. Democrats and Republicans alike must be able to trust that when a deal gets signed into law, it will be followed.

Senator Collins reportedly felt “unease.”

I am concerned if the Trump administration is clawing back money that has been specifically appropriated for a particular purpose

But not uneasy enough to affect her vote. It’s the end times for our old political system. The old bulls are going to the slaughter.

Going forward, this newsletter — as always, focused on power — will work to sketch out a pathway to rebuild a new legislature from its charred remains, cheer on any signs of life, and point out places where we went wrong.

Funding the Committees

This upcoming week, the House of Representatives will work to divvy up funding to its committees. For decades committees were the legislative workhorses of Congress. This changed startnigin the mid-90s, which much of their power attenuated by a series of funding cuts and, in the House, a power grab by leadership. How did we get here?

Let’s start with a look at total funding levels for committees in the House going back to the 102nd Congress. This data is really hard to gather, but I’ve synthesized it into a nifty chart, and I’ve even adjusted for inflation.

Starting in the mid 1990s, committee funding levels rose from a low of $274 million to $547 million in the 2010, crashed around 2013 at $396 million, and in the last Congress rose to about $468 million. Yes, we’re $79 million below recent peak funding.

The best way to understand the modern story of committee funding starts with Newt Gingrich cutting funding for the Legislative Branch as part of the Republican revolution, then, the slow restoration of funding through the Bush and Clinton administrations until it hit a peak under Nancy Pelosi, and then was drastically cut under Boehner, who was rushing to meet the demands of the tea party and rising Republican revolutionaries.

During this time, demands on Congress grew but available resources were unequal to the task. As far as we can tell, committees responded to the dire funding environment by reducing the number of senior staff, reducing pay for staffers, and reducing the quality of their work. Unfortunately, data on individual committee staffing levels is hard to come by, and some information — such as caps on the total number of committee staff — is not publicly available.

Not all committees are created equal. Some are much better funded than others. This chart shows funding levels for each of the House’s committees at 10 year intervals. Some things should be immediately apparent.

The first is that appropriators receive a lot more money than any other committee. In the 118th Congress, appropriators received $62 million, compared to Oversight’s $30 million, Energy and Commerce’s $27 million, and down it goes to roughly $8 million for the smallest committee (not counting Modernization, not included, which is a pittance of that). Here’s how the pie looked for the 118th Congress.

The second take-away is the huge fluctuation in committee funding levels over the last few decades. Most committees were funded at higher levels in the 108th and 118th Congresses than in the 113th. That funding churn leads to staff churn and loss of expertise. So too does the alternation of who is in the majority, which results in the new minority party firing half their staff when they lose power.

If you zoom out, funding for House committees has roughly stayed flat (with big fluctuations) while at the same time all the new money in the legislative branch has gone to the Capitol Police and the Architect of the Capitol. I’m not going to walk through that here, but I will link to a report where I went into it all in more detail. The following chart shows where those new funds have gone as of 2020.

So why tell you all this now? This Tuesday and Wednesday the Committee on House Administration will be holding hearings where the Chair and Ranking Member of nearly every House committee will testify. The committees must come and ask for funding for their operations. The House Administration Committee, which is composed of leadership appointees, will consider their requests and generate a resolution to allocate funds for the committee.

Let’s step back for a second and talk where the money comes from. Every year Congress enacts the Legislative Branch Appropriations bill that provides roughly $7 billion to fund all of the operations of the legislative branch. That bill contains a number of line item provisions.

One provision provides funding for committee employees (not including appropriators).

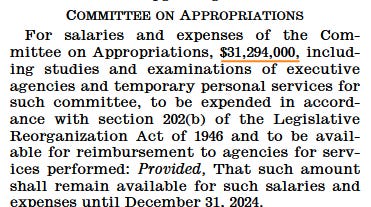

Another provision provides funding for the appropriations committee.

(There are other complicating factors that I will largely skip over to save your sanity, primarily concerning how the appropriations cycle and the committee funding cycle are largely out of sync.)

What matters here is that by the time we get to the committees asking for funding from House Administration, the total amount of funds for the committees was decided months ago in the Appropriations bill.

Not only that, but the congressional committees asking for funds, the Committee on House Administration, and even the House Legislative Branch Appropriations Subcommittee (which itself is tremendously understaffed) likely have little visibility into these long term trends discussed above.

As far as I know, there is no great source within Congress that tracks and makes available to members this kind of funding data at this level of detail. There should be.

Congress should have an earnest discussion about what it takes to properly fund committees, to properly staff committees, and what outcomes are expected. As things stand now, committees are ill-equipped to manage their current workloads, let alone resist an over-reaching White House and power-consolidating congressional leadership that’s been slowly pulling the rug out from under them.

(The Senate Rules Committee can be expected to hold their own hearings on funding Senate committees in the near future. )

What are the committee requests?

I had hoped to have a comparison for you of what each House committee is requesting this Congress versus last Congress, but as of Friday afternoon, Education, Ethics, Foreign Affairs, and Small Business have not introduced their funding resolutions. I won’t have data for Appropriations, which is funded through a different process, and there’s no resolution for House Administration.

What I can tell you is there’s a huge range of requests, ranging from a 40% increase requested by the Judiciary Committee to a flat budget from the Budget committee. You *should* be able to sort the chart below by “dollar change” and “percent change.”

The big winner is the Judiciary Committee, which has requested the largest percentage change (40%) and change in real dollars ($9m), followed by Ways & Means for dollar amount ($6m) (25%).

Oh, the hypocrisy

NOTUS has a fun story that members of the House routinely give their voting cards to other members to vote for them when it’s too inconvenient to go to the House floor. (Sometimes they give their voting cards to non-members, too.) This practice is prohibited by the House Rules — members cannot authorize other people to cast their votes.

Many of the representatives engaging in in-person voter fraud — yes, that’s right, I said it — are Republicans. I could make a joke about requiring them to show their government-issued photo ID every time they vote, but I’m above that kind of thing.

The reason this longstanding practice has come up is because some members want to allow new parents to be able to vote remotely. They argue, not unreasonable, that Congress should flex a bit when their kids are infants. They point to the hypocrisy of their colleagues, who are too lazy to walk to the floor from the cloakroom (or perhaps further away), while these members want to do their jobs (remotely).

There is a real distinction between having the member vote themself, whether in person or remotely, versus giving your voting card to another member. In the first instance, the duly elected member remains in control of their vote. In the other, well, YOLO.

Many national legislatures have solved the issue of accurately verifying members who vote, whether in person or remotely. In fact, during the COVID pandemic, Newt Gingrich himself testified before the House Admin Committee that he saw no technological problems with being able to identify members voting from afar. The policy issues he raised also don’t apply for extenuating circumstances, like pregnancy.

Now, we could require members of Congress to use biometric identifiers or some other tool to make sure that only the member has cast their vote. Or we could treat all members like adults, empower them to vote in person and (in limited circumstances) vote remotely, remind them of the rules, and call it a day.

This week

Thus far the House doesn’t have any major legislation scheduled for the floor, with the big behind-the-scenes action being efforts by House and Senate Republicans to work out a reconciliation bill (or two). It may be that the Senate goes first. We are rapidly approaching the end of the appropriations continuing resolution, on March 14th, and news reports suggest that the House and Senate’s top line numbers are not close.

The Senate is expected to consider several nominations on the floor, including Tulsi Gabbard for Director of National Intelligence, Robert F. Kennedy for Health and Human Services Secretary, Howard Lutnick for Commerce Secretary, Brooke Rollins for Agriculture Secretary, and Kelly Loeffler for Small Business Administration administrator.

There are 34 committee meetings scheduled across the two chambers, including a few appropriations hearings in the House. Some committees are still holding their organizational meetings. Senate Labor will hold a nomination hearing on the Secretary of Labor, Senate Judiciary will hold a nomination hearing on the nomination of Kash Patel to be FBI Director, and Senate Health will hold a hearing on the nomination of Linda McMahon to be Secretary of Education. House Judiciary will hold a hearing on “reining in the administrative state” and House Foreign Affairs will look at “the USAID betrayal.”

Odds and ends

Current and former Members of Congress seeking backpay for unconstitutionally denied Cost of Living Adjustments appear to have prevailed (in part) in federal court. An opinion issued on February 4th finds that claims for denied COLA’s for 2018 going forward are permissible, but not claims from prior that date, nor claims regarding unpaid retirement or thrift savings plans. It appears the next step may be appeals of the ruling to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.

How much longer can the current administration strike down Biden regulations? The Coalition for Sensible Safeguards has a CRA tracker.

Bob Bauer and Jack Goldsmith argue the flurry of Trump administration executive orders is to “effectuate radical constitutional change.” They discuss the EO process and the role of the DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel. I think Bauer and Goldsmith are a bit too cute, however, as the Office of Legal Counsel was never the restraint that they assert it was. Nonetheless, they argue the White House is making a different play:

They are, rather, bombarding the Court with a wave of legal challenges about the proper scope of Article II (among many legal issues) with the aim of provoking a confrontation over the legitimacy of the existing legal order, at least with regard to Article II, and perhaps more broadly. And the administration might be planning to dare the Court to say “no” with threats of noncompliance.

Congratulations to our friends at GSA for reestablishing that agency’s gsa.gov/open webpage.

To kick off Valentines Day, the Office of the Whistleblower Ombuds will hold a pop-up tabling event in the Longworth Dunkin Donuts on February 13th from 2:00pm-3:30pm. Stop by and meet the whole team, pick up their latest guides, and get your questions answered on how your office can work effectively with whistleblowers from the public or private sectors. Complimentary donuts and coffee will be available!

More firings. The Trump administration loves to fire people by Tweet on Friday night — it’s both cruel and often violates federal law (which requires notice to Congress). On Friday, the White House Director of Presidential Personnel tweeted that Trump had fired the non-partisan Archivist of the United States, Colleen Shogan.

Where are the comity police? For years and years, I’ve heard what I imagine are well-intentioned lectures on the importance of comity, usually aimed at folks on the left. Well, friends, here’s your chance to speak up when the shoe is on the other foot. Example 1. Example 2.

Any idea why appropriators get/ need so much more funding than other committees?

Excellent article. One thing that everyone in Congress ignores is Article I, Section 8

making the majority of the things on the list as unconstitutional spending.