Protecting Congress Starts With Police Reform

Minnesota’s Tragedy Should Spur Further Reform at the Heart of Congressional Security

Saturday's tragic assassination of Minnesota House Democratic leader Melissa Hortman and her husband Mark and attempted assassination of Minnesota Senator John Hoffman and his wife Yvette are resonating in Congress, heightening fears about the security of federal legislators.

Anxiety about political violence is not only reasonable, it is grounded in a grim pattern of recent events. The October 28, 2022 attempted murder of Speaker Pelosi's husband Paul Pelosi as part of an effort to kidnap the Speaker. The January 6, 2021 Trump insurrection that constituted an attempt to overthrow Congress and murder elected officials. The June 14, 2017 Congressional Baseball shooting where James Hodgkinson attempted to murder Republican officials, wounding four people including then-House Majority Whip Steve Scalise.

It isn't only Congress that has been targeted for violence. Cody Balmer was charged with the April 13, 2025 attempted murder of Pennsylvania governor Josh Shapiro. Ryan Routh attempted to assassinate now-President Trump on July 13, 2024. 13 men were arrested on October 8, 2020, for attempting to kidnap Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer and overthrow the state government. There also has been political violence aimed at lower officials and regular citizens.

Tragically, violence is as American as apple pie. Every society has some level of political violence. In ours, it is made more dangerous by the availability of amplifying weapons, such as firearms. In addition, outbreaks of violence may increase as divisions in society are stoked, amplified, and reflected back by political leaders whose words and deeds increase the risks both of stochastic terrorism as well as organized attacks.

Violence is not historically uncommon, including political violence. In her book on 19th century Congress, Joanne Freeman recounts "more than seventy violent incidents between congressmen in the House and Senate chambers or on nearby streets and dueling grounds" between 1830 and 1860. She describes "hand-to-hand combat and rioting at polling places," violence at state legislatures, including "an all-out row in the Illinois legislature featuring 'considerable wrestling, knocking over chairs, desks, inkstands, men, and things generally."

In 1837 Arkansas, "when a representative insulted the Speaker during debate, the Speaker stepped down from his platform, bowie knife in hand, and killed him." The Speaker was acquitted for excusable homicide, reelected, only to pull his knife on another legislator – and stopped only when his colleagues cocked their pistols at him.

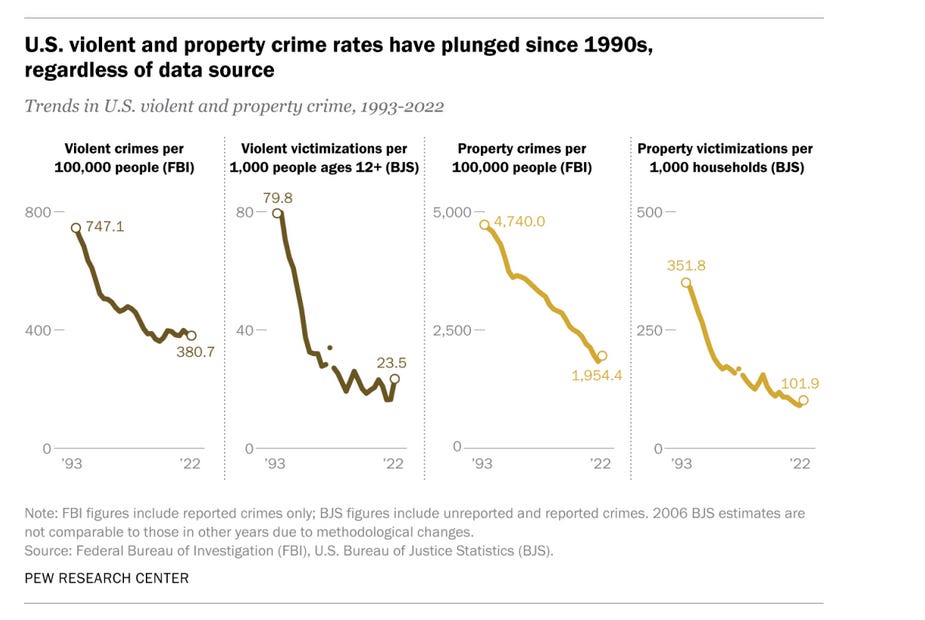

Over the last 40 years, violent crime in the US has dropped by 49%, according to Pew Research. People perceive crime as increasing despite this significant downward trend. I did not find any data on the trends in political violence. But we can easily recall the assassinations and attempted assassinations of Reagan, JFK, RFK, MLK, Teddy Roosevelt, McKinley, Lincoln, plus the organized violence against supporters of civil rights, free labor, and many other movements.

To my knowledge, there are no public experts on congressional security. I've been following and writing about congressional security for more than a decade and there is no appetite from foundations to support this work and little interest from journalists in reporting on what's uncovered. Only when there is an incident is there any attention, and it quickly dissipates.

In of itself this is not necessarily a problem assuming there are sufficient internal feedback mechanisms to focus the attention of security forces. Generally speaking, this is not the case. Prior to January 6, 2021, the U.S. Capitol Police were the least transparent and accountable entity in the federal government. Despite an enormous budget, they were a poorly led, poorly organized, poorly managed agency that fell apart when faced with a real test. The absence of real oversight and accountability mechanisms led to an enormous, expensive, incapable, insular paper tiger.

Since then, we have seen some reforms at the Capitol Police. The Capitol Police Board is more responsive to its congressional overseers. The Chief can now directly call the national guard. There is the consolidation of intelligence activities including the ability to gather information and perform their own intelligence assessments. They've newly purchased and pre-positioned equipment to respond to threats. They've provided significant support for member residential security.

There's also better training for officers. Officer starting pay is $81,552 annually, plus good retirement benefits, a health and fitness program, help with student loans, union protections, and more. (Many officers earn significantly more than the staff they protect and they are eligible to earn significant overtime.)

The prior USCP leadership was actively hostile to the press and civil society. This is no longer the case. They are using social media and holding press conferences as the situation warrants. Perhaps of more debatable value, the USCP is creating regional offices and funding special U.S. attorneys to prosecute cases.

But, as I wrote in my testimony before Congress in February 2022, "The leadership structure of the Capitol Police, as embodied in the Capitol Police Chief and the Capitol Police Board, make virtually certain that we will be unready to address grave threats to the continuity of Congress in the days, months, and years ahead."

It's also notable that when the press conducted their exit interviews of Capitol Police Chief Manger earlier this year, not a single interviewer quoted someone from outside the department with any knowledge of its operations. Only one journalist challenged the Chief's claim of increasing threats against members by asking how many threats are substantiated – and did not get a clear answer. The former Chief did not provide a clear answer when he testified before Congress, either. He suggested there were hundreds of substantiated threats while also publishing a press release asserting almost 9,500 "concerning statements and direct threats." It is possible that the USCP statements, stripped of context of the number of substantiated claims, arrests, prosecutions, and convictions, have the unfortunate effect of overly stoking member fears.

Despite reforms, core structural flaws remain. Among them:

The Capitol Police Board structure makes no sense. The Sergeant at Arms of each chamber is on the Board, but their jurisdiction is significantly smaller than the USCP and their focus is narrowly on their chambers and not the Legislative branch as a whole.

The Board only has one full-time staffer, which imperils independence and institutional memory.

The House and Senate cannot hold a hearing with all members of the USCP Board. As one member of the Board is always from the other chamber, they refuse to participate. For example, the Senate Sergeant at Arms will not sit before a House hearing, and vice versa. This impedes oversight.

The Inspector General is not independent of the Board, and does not possess the authority to oversee the Board.

Despite Congressional direction, fewer than half of the US Capitol Police Inspector General reports have been published on the agency's website. The reports cannot be published without the approval of the USCP Board. No reports have been published for 2025. No reports are on the central IG website oversight.gov.

The Capitol Police have not published their semi-annual spending reports since 2017, despite the legal requirement under 2 USC 1910. These reports are required to be made publicly available – they are supposed to be published as House documents.

The new Public Records request policy, directed by Appropriators to be modeled after the FOIA, is anything but. They routinely deny records requests that FOIA offices would grant. There is no online log of requests and they will not provide one. The USCP's process was not created in consultation with the public, as appropriators had directed.

There is no non-USCP engagement body, composed of members of congress, staff, journalists, lobbyists, and local residents, to regularly communicate with the USCP leadership.

The USCP only publishes a subset of its weekly crime summary and it is not possible to know what is being held back. (Is it only minor arrests, such as for protests, or is it more?)

I mention all this not to criticize the Capitol Police, but to provide context. In the last five years, they have made significant progress in moving towards a security focus instead of a policing focus. The Board's appointment of Michael Sullivan as the new USCP chief, to be sworn in on June 30th, provides an opportunity to make progress on many of these issues.

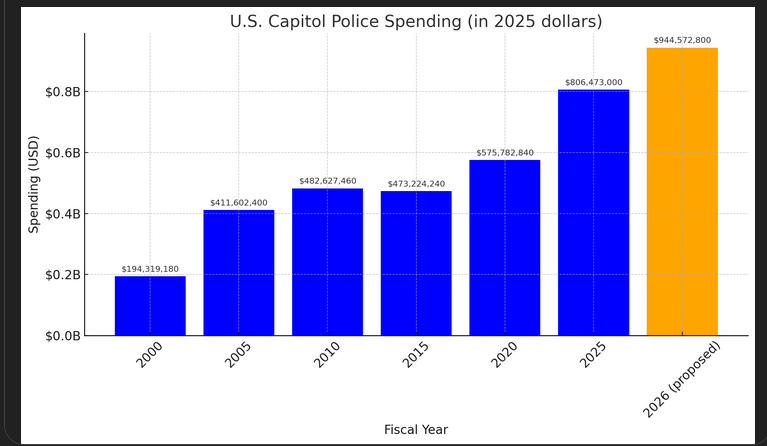

Member concerns about their safety have long driven funding and personnel increases for the USCP, who employ more than 2,300 officers and several hundred "civilians." The USCP's goal is to reach 2,530 sworn personnel by the end of FY 2026, plus hundreds of others. This contrasts with a severely diminished Legislative branch, which over the decades has eliminated thousands of policy positions and generally relies on more junior staff.

How can Congress protect itself? A public accounting of the operations of the dignitary protection unit – part of the protective services bureau – would be helpful. The last IG report on them dates back to 2019 and concerns their overtime pay.

So too would be a revising of legislative branch plans concerning continuing of operations, an issue that could come up in a mass casualty event. The assassinations in Minnesota may temporarily change political control of the legislature. We should listen to former Rep. Brian Baird and remove that incentive for those who would attack members of Congress.

We should rethink how we fund, oversee, organize, and hold the Capitol Police and its Board accountable. The location of the Capitol Police’s budget as non-defense discretionary appropriations inside the Legislative branch bill is constraining their funding and cannibalizing funding for policy-making. We should fix that. In doing so, we must make sure they're aligned with a secure and open Congress.

There will be an impulse to make members less accessible to the public. We should resist such an urge. There also will be an impulse to turn the Capitol complex into a fortress. We should resist that urge as well.

The danger in part is driven by the way we practice our politics – which is driven by how we set up our institutions. Now is the time for reform.